The management of myopia is typically practitioner-led by professionals and innovative eyecare softwares. Currently, the standard of care is to provide single-vision spectacle or contact lenses to eliminate the blurred vision symptoms, which are characteristic of myopia. Symptom-based management does little to address the underlying cause of myopia development or progression, nor does it affect the risks of eye disease development as a consequence of the excessive axial elongation caused by progressive myopia. This approach to clinical care is problematic from a population health perspective for three key reasons.

As Covid-19 is now painfully demonstrating, public health approaches to disease management are motivated by the risk of

(i) large scale human death, disability and/or quality of life impact

(ii) healthcare service incapacitation

(iii) global economic disruption

Myopia is an established risk factor (second only to age) for the development of glaucoma, cataract and retinal detachment. Also, it is the primary risk factor in myopic macular degeneration. Even in countries where the prevalence is low relative to Asia, myopia is a leading cause of vision impairment. It includes a substantial proportion of the 116 million cases of moderate to severe vision impairment and 7 million cases of blindness due to uncorrected refractive error.

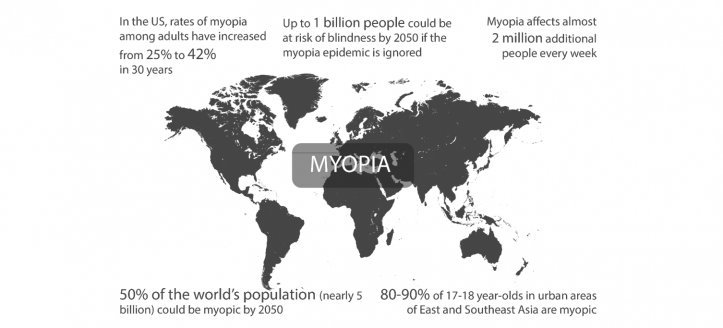

Myopic macular degeneration already accounts for an additional 10 million people with vision impairment, including 3.3 million blind despite refractive correction (almost double the numbers affected by glaucoma), and it is expected to grow six-fold by 2050. As a leading cause of vision impairment and blindness worldwide, myopia is undoubtedly a source of disability and quality of life loss. The economic costs are already huge, estimated at more than $250 billion per annum and growing. With 2 billion myopes currently (which is projected to reach 5 billion by 2050 as per Figure 1), the threat to eye care service sustainability is also very real. Myopia, therefore, meets all the criteria necessary to justify a global public health response, but this has yet to be politically prioritized in any meaningful way.

Figure 1: The Myopia Map: A global epidemic

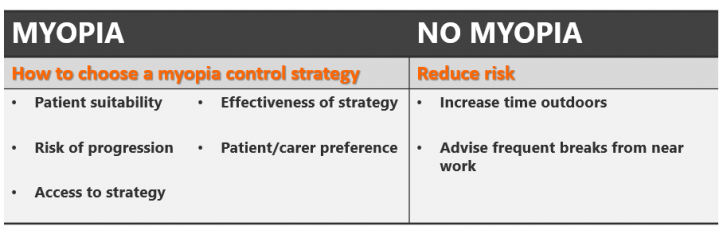

The public health priorities in dealing with myopia are two-fold: (i) to prevent myopia onset where possible; and (ii) to mitigate the risk of ocular diseases such as retinal detachment and myopic macular degeneration and associated vision loss in those who become myopic. Public health strategies can be practitioner-led, involving health promotion activities provided to those attending primary care settings, or population-based where the entire population is targeted.

The primary care and population health approaches should, however, be complementary. Complete prevention or delayed onset (later onset is associated with slower progression) would be ideal. Among children who have already become myopic, altering the rate of progression can still reduce the lifetime risk of progression to high myopia and disease development. Eye health practitioners can primarily contribute to the latter by implementing a personalized risk-based management approach for the treatment of individuals with progressive nearsightedness.

The risk-based approach involves prescribing individualized, evidence-based treatments and behavioral modifications that slow or prevent continued progression. This form of clinical care targets the intrinsic physiology of eye growth by modifying optical defocus, altering growth signaling or motivating behavior change to reduce exposure to known risk factors. These practitioner-led strategies provide additional choices to those at risk, which may or may not be adopted as they can involve additional cost or inconvenience and because parental awareness of the risks of myopia is low.

.png)