.png)

Author: James Loughman

5 December 2017

Myopia - A Global Epidemic

As noted in a 200th anniversary article for the New England Journal of Medicine, “Disease has changed since 1812”. The great epidemics of the past were almost invariably infectious, and the leading causes of disability and death included conditions such as tuberculosis, pneumonia and influenza. Today, medical attention has shifted to new epidemics of chronic disease, many of which are a result of changes to our lifestyle and environment. Such changes include increasing time in education, more sedentary lifestyles, technological advances and ever-increasing rates of urbanisation.

One of the conditions that more than meet the criteria for consideration as a modern and global epidemic is Myopia. Perhaps better known as short-sightedness or nearsightedness, myopia is the most common and fastest growing eye condition worldwide.

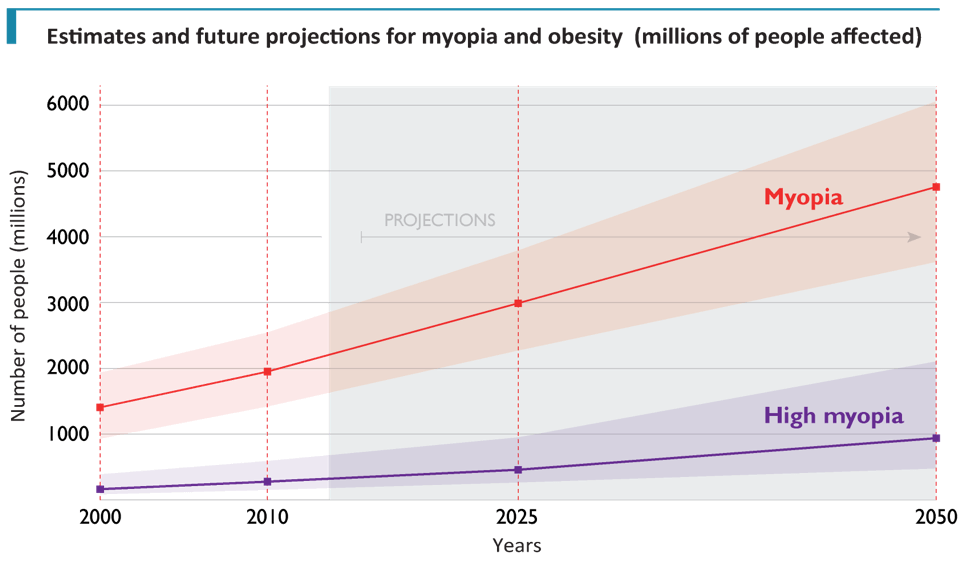

Adapted from: Holden, B. A. et al. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. (2016).

Only one meta-analysis has been conducted to evaluate the temporal change in global myopia prevalence. The analysis extends back only to the year 2000 but indicates that the global prevalence of myopia has increased more than 35% in the period from 2000 to 2015; with absolute numbers of people affected increasing by almost two-thirds to just under 2.3 billion. The rise in high myopia has been even more dramatic. By 2015, prevalence had increased by 75% to affect 4.7% of the world’s population, while the absolute numbers affected had more than doubled to 344 million worldwide.

By 2050, it has been projected that the number of people affected by myopia will more than double to a staggering 5 billion, or one in every two persons. High myopia will affect three times more people than current levels, such that more than 1 billion will have pathological myopia, and be at significant risk of blindness.

The extraordinary and rising prevalence of this modern epidemic, when compared to its infectious predecessors, represents a very different and, in some ways, infinitely more complex threat to society.Whereas the origin and nature of infectious epidemics were essentially biological, the aetiology of myopia exhibits a much more variable mix of genetic, socioeconomic, cultural, lifestyle and environmental factors. Such intricate origins make this condition fundamentally more difficult to address. There isn’t a simple pill, injection or another basic set of public health interventions that can control or eradicate it. Instead, myopia control will require a comprehensive portfolio of strategic interventions to generate sufficient population-level impact. This will include the generation of critical evidence to inform the necessary policy and practice change, along with extensive advocacy among government and all stakeholders including parents and practitioners in relation to the need to tackle myopia.

It is up to us as primary eye care practitioners to raise awareness of this silent epidemic and alter our clinical practice as a means to control it.

Suggested further reading:

- Holden, B. A. et al. Global Prevalence of Myopia and High Myopia and Temporal Trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. (2016).

- Flitcroft, D. I. The complex interactions of retinal, optical and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. (2012).

- Holden, B. et al. Myopia, an underrated global challenge to vision: where the current data takes us on myopia control. Eye (Lond). (2014).

James Loughman is the Clinical Research Director for Ocuco Ltd.

An Optometrist with more than 20 years of clinical, academic, research and management experience, James recently joined Ocuco as Clinical Research Director. James is also presently the Director of the Centre for Eye Research Ireland, a research facility based in the Dublin Institute of Technology, the same university where he received his PhD in 1997; James oversees a portfolio of research including technology development and big data analytics projects alongside various clinical trials for the control of myopia, glaucoma and other blinding conditions.